doi: 10.56294/hl2024.408

ORIGINAL

Insights into the Experiences of Family Caregivers in Intellectual Disability and Dementia

Reflexiones sobre las experiencias de los cuidadores familiares en la discapacidad intelectual y la demencia

Komal Patel1,

Bikrant Kumar Prusty J2 ![]() , Tarang Bhatnagar3

, Tarang Bhatnagar3 ![]() , Abhinav Mishra4

, Abhinav Mishra4 ![]() , Jamuna KV5

, Jamuna KV5 ![]() , Ajit Kumar Lenka6

, Ajit Kumar Lenka6 ![]() , Dhanaji Wagh7

, Dhanaji Wagh7 ![]()

1Parul University, PO Limda, Tal. Waghodia, Department of Gynaecology, District Vadodara, Gujarat, India

2IMS and SUM Hospital, Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Department of Paediatrics, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India.

3Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India.

4Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, India.

5Department of Forensic science, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University), Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

6School of Allied Health Sciences, Noida International University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India.

7Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences, Krishna Vishwa Vidyapeeth “Deemed to be University”, Dept. of Physiology, Taluka-Karad, Dist-Satara, Maharashtra, India.

Cite as: Patel K, Bhatnagar T, Mishra A, Jamuna K, Kumar Lenka A, Wagh D. Insights into the Experiences of Family Caregivers in Intellectual Disability and Dementia. Health Leadership and Quality of Life. 2024; 3:.408. https://doi.org/10.56294/hl2024.408

Submitted: 16-03-2024 Revised: 04-08-2024 Accepted: 08-11-2024 Published: 09-11-2024

Editor: PhD.

Prof. Neela Satheesh ![]()

ABSTRACT

Research is based on interviews with prospective service users and their caregivers; this research lays the groundwork for developing a structure for designing supports and removing obstacles for people with intellectual impairment & dementia. It is essential to contain persons through intellectual impairments & dementia in accessibility inquiry because they have unique perspectives to offer. Research aims to use first-person and caregiver accounts to comprehend better the environment’s impact on regular activity engagement among adults with intellectual impairments and dementia. Twelve family and professional caregivers attended five regular focus groups, while four persons with intellectual disability and dementia took part in two sessions of the fictitious group method. The results of sessions using the nominal group approach were studied through the lens of the environment, and the resulting transcripts were subjected to thematic analysis. Activity accessibility, caregiver help, social connections, duties, confidentiality, and wellness and health were highlighted as six essential themes by participants with intellectual disability and dementia. Caregiver involvement brought insight from more expansive ecosystem levels to their narrow, immediate-environment-focused viewpoints. These included dementia-friendly like medical facilities, healthcare facilities, group environments, conveyance, retains or retailers, individuals incorporated dementia-related knowledge, volunteer, and participation opportunities.

Keywords: Intellectual Disability; Dementia; Down Syndrome; Caregivers.

RESUMEN

La investigación se basa en entrevistas con posibles usuarios de servicios y sus cuidadores; esta investigación sienta las bases para desarrollar una estructura que permita diseñar apoyos y eliminar obstáculos para las personas con discapacidad intelectual & demencia. Es esencial incluir a las personas con discapacidad intelectual y demencia en la investigación sobre accesibilidad, ya que tienen perspectivas únicas que ofrecer. La investigación pretende utilizar los relatos en primera persona y de los cuidadores para comprender mejor el impacto del entorno en la participación en actividades regulares entre adultos con discapacidad intelectual y demencia. Doce cuidadores familiares y profesionales asistieron a cinco grupos focales nominales, mientras que cuatro personas con discapacidad intelectual y demencia participaron en dos sesiones del método de grupo ficticio. Los resultados de las sesiones en las que se utilizó el método de grupo nominal se estudiaron a través de la lente del entorno, y las transcripciones resultantes se sometieron a un análisis temático. La accesibilidad a las actividades, la ayuda del cuidador, las conexiones sociales, los deberes, la confidencialidad y el bienestar y la salud fueron destacados como seis temas esenciales por los participantes con discapacidad intelectual y demencia. La participación de los cuidadores aportó una visión de los niveles más amplios del ecosistema a sus estrechos puntos de vista centrados en el entorno inmediato. Éstos incluían la demencia-amistoso como instalaciones médicas, instalaciones del cuidado médico, ambientes del grupo, transporte, retiene o los minoristas, individuos incorporaron el conocimiento dementia-relacionado, voluntario, y oportunidades de la participación.

Palabras clave: Discapacidad Intelectual; Demencia; Síndrome de Down; Cuidadores.

INTRODUCTION

Family caregivers play a vital role in the treatment of dementia patients, especially in nations. People who have cognitive impairments in India are often cared for by their family. Dementia patients’ care needs increase as their mental and physical well-being deteriorates, and they can become difficult to manage behaviorally. The parents also have much to deal with financially, physically, socially, and mentally. (1) It is challenging to meet the medical needs of native people on a continuous basis. Federal in Character and territorial governments, various ministries and agencies, the range of services available varies widely among jurisdictions and policy domains. These models include joint or tripartite deals that outline how funds and service delivery will be coordinated. Not often do indigenous peoples’ methods of existence, being aware and believing factor into the planning, creation, or delivery of services. (2) Examining the family bonds of people who take care of friends and relatives with dementia could help shed a spotlight on the effects of the caregiver-relative with dementia relationship. Caregivers have emphasized the need for, or desire for, good family network assistance. The caregiver and family members faced clear communication barriers contextualized differently in each household. To better advocate for family caregivers, offer clinical support, and help families become more unified, psychological nurses require a deeper understanding of family connections.(3)

Over 11 million people in the offer voluntary care for a family associate or comrade who has Alzheimer’s illness or additional type of dementia. As dementia worsens over time, family members often take on more and more of the caregiving responsibilities. Caregiving responsibilities for a loved one could be extensive, including but not limited to medication management, food assistance, transportation aid, and healthcare making choices. An interdisciplinary education model is the most effective way to meet the varied educational requirements of family caregivers, and its importance in providing family-centered care is widely acknowledged.(4) Informal carers have advocated for the government to create and execute an initiative of integrated assistance to fulfil their requirements better, encourage more employee involvement, facilitate a better balance between job, personal life, and parenting obligations, and mitigate negative effects on their psychological and physical well-being. There is a shortage of flexible, self-paced, and free online dementia education and skills training courses for informal carers, despite over 80 % of people using the World Wide Web to research medical subjects. Furthermore, the government provides funding for dementia and elderly care under the “Aged Care Act 1997,” governed by a consumer-driven and person-centred care policy.(5) People with intellectual impairments remain alive longer than ever before, and many of them may eventually need hospice treatment due to serious diseases. Death rates from illnesses requiring hospital services were not tracked. Few referrals are made to specialized comforting care facilities, & there is no suggestion that palliative care adequately supports persons with intellectual impairments and their careers.(6) This research seeks to address the insights into the experiences of family caregivers in intellectual disability and dementia.

In Sweden, Dementia sufferers often remain in their own residences and are cared after by family and friends. Taking care of a family member can be a good thing. It may also be harmful because it can be hard to see signs like disruptive conduct and false beliefs. Studies have shown that family caregivers’ worth of life reductions as an outcome of the stress involved in delivering care. To gauge community sentiment on a proposed mobile app designed to aid healthcare professionals in assisting family members in managing a home-dwelling person with dementia. Eight one-on-one interviews with family caregivers and one focus session with dementia specialists from the medical community were analyzed using content analysis techniques.(7) Intellectual Disability Dementia Care Pathways (IDDCPs) should be better understood, together with the hardships and assistance requirements to those who precaution for individuals with intelligentdebilities& dementia, both professionally and personally. Caregiver perspectives on the impact of IDDCPs and other types of support were analyzed. The approach used was grounded on the philosophy of constructivism the data was gathered via semi-structured consultations with ten carers (2 family caregivers, 8 paid caregivers, &8 healthcare authorities).(8)

There is pain associated with dementia. In order to provide the best possible conclusion of life to attention, the suffering of those with advanced dementia must be taken very seriously. The research’s overarching objective was to evaluate the influence of carers’ distress on their treatment options for persons with severe dementia.(9) Dementia caretakers were asked to fill out a cross-sectional survey, with some of them being selected to engage in focus groups to glean even more information. Caregiving for a loved one with dementia may adversely affect a caregiver’s health and happiness. Multiple research approaches were used to investigate how the global epidemic affected family caregivers.(10) The research on giving up driving aimed to understand better how people deal with and adjust to such a significant change in their lives. To investigate how healthcare practitioners and family caregivers of people with dementia conceptualize the emotional reactions of dementia-diagnosed drivers and ex-drivers. People’s identities may be severely shaken when they have to give up chauffeuring, and this loss is often compounded by other losses, such as their ability to be independent as dementia progresses.(11) The research sheds light on the difficulties faced by family caregivers as they prepare to hand over care for elderly loved one who has dementia. Building trust and self-assurance between residential aged care services (RACS) and family caregivers is crucial. Geriatric care nurses may play an essential part in this by fostering honest dialogue and close bonds with residents and their loved ones.(12)

The difficulties encountered by dementia caregivers in Pakistan were investigated using semi-structured consultations. The research was undertaken as portion of a more comprehensive subjective investigation of dementia in Pakistan. A total of 14 female caregivers (ages 35 to 80) were interviewed for this research. The majority of the research’s carers had college degrees and decent incomes. In-depth discussions were held in Urdu, translated into English, and analyzed topically.(13) Although persons with dementia and their carers experience significant distress due to behavioral and emotional signs, little is known about how family caregivers see the treatment of these symptoms. Caregiver perspectives on the behavioral and psychological symptoms of their loved ones with dementia, coping strategies, and how those perspectives have evolved since the 2009 COVID-19 pandemic were investigated. Twenty-one family carers were interviewed remotely utilizing an ethnographic, interpretive approach with continual comparative methods.(14)

METHOD

The methods and capabilities of those alive with dementia & their domestic caregivers towards DFCs were investigated using a qualitative content analysis approach. Understanding the studied phenomena required the application of qualitative content analysis, which organizes manuscripts into classifications by the organized coding & identification of melodies or designs in the text.

Design

Exploratory qualitative research methods were employed in this research, including focus discussions and fictitious group method sessions, to recognize well involvements of adults through intellectual injury & dementia. Ecological systems theory is valuable for analyzing how different settings affect people’s involvement propensity. A person’s immediate context is considered a microsystem consisting of their actions, responsibilities, and relationship with others; more significant aspects involve navigating remote systems, social taxes, and past encounters.

Datasets

Neurologists and daycare centers recommended the 19 people with dementia who fit the research’s requirements. Only 16 were willing to take part. The mean age (standard deviation) of the 16 dementia patients was age group between 35 to 96, and nine 52,2 % of the patients were female. Dementia severity was ranked as follows: 10 mild, 3 moderate, and 2 mild cognitive impairment are represented in table 1.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics |

||||

|

Characteristic |

Caregivers, N (%) |

Caregivers’ care receivers with dementia, N (%) |

Participants with dementia, N (%) |

|

|

Age |

35-85 |

58-96 |

56-88 |

|

|

Services/Resources used |

||||

|

Family support group |

- |

31,2 % |

0,01 % |

|

|

Gender |

||||

|

Male |

16,1 % |

52,2 % |

45,8 % |

|

|

Female |

88,2 % |

51,1 % |

44,9 % |

|

|

Current dementia level |

||||

|

Moderate to severe |

0 |

- |

2 |

|

|

Moderate |

3 |

- |

8 |

|

|

Mild to moderate |

2 |

- |

0 |

|

|

Mild |

10 |

- |

10 |

|

|

MCI |

1 |

- |

0 |

|

Measure

To obtain this session, using the standard group approach, a method that is becoming more common for persons with cognitive challenges, were framed around the query: As one getting older, what helps they do the things you need and want to do and what doesn’t help they do these things? The subject matter group followed an established informal format, asking caregivers a total of four questions about the role that physical, psychological, and social variables played in determining whether or not people with an intellectual disability or dementia took part in regular tasks and habits. The questions posed in the focus groups encouraged introspection about the perspectives of care receivers and the caregivers themselves.

Procedures

The actions involved finding research volunteers, screening them, and getting their permission. The cognitive accessibility of consent forms was optimized for individuals with intellectual impairment. Each parent was queried on their familiarity with the concept of a diagnosis, following the lead of previous studies in this area. Because of this, neither the words “dementia” nor “Alzheimer’s” appeared in any of the materials used to recruit, screen, or get permission from persons with intellectual disability. They hosted two nominal group method sessions for individuals with quick impairments dementia & five conventional attention group discussions with caregivers from two different organizations that worked together on this project. There were only one to four people in each 60- to 90-minute session. In the second session, using the nominal group approach, the participants discussed the topics that had received the most votes in the first session. Under the established protocol, members of the caregiver focus groups answered and debated the issues posed to them.

Dementia experiences in individuals with intellectual disabilities

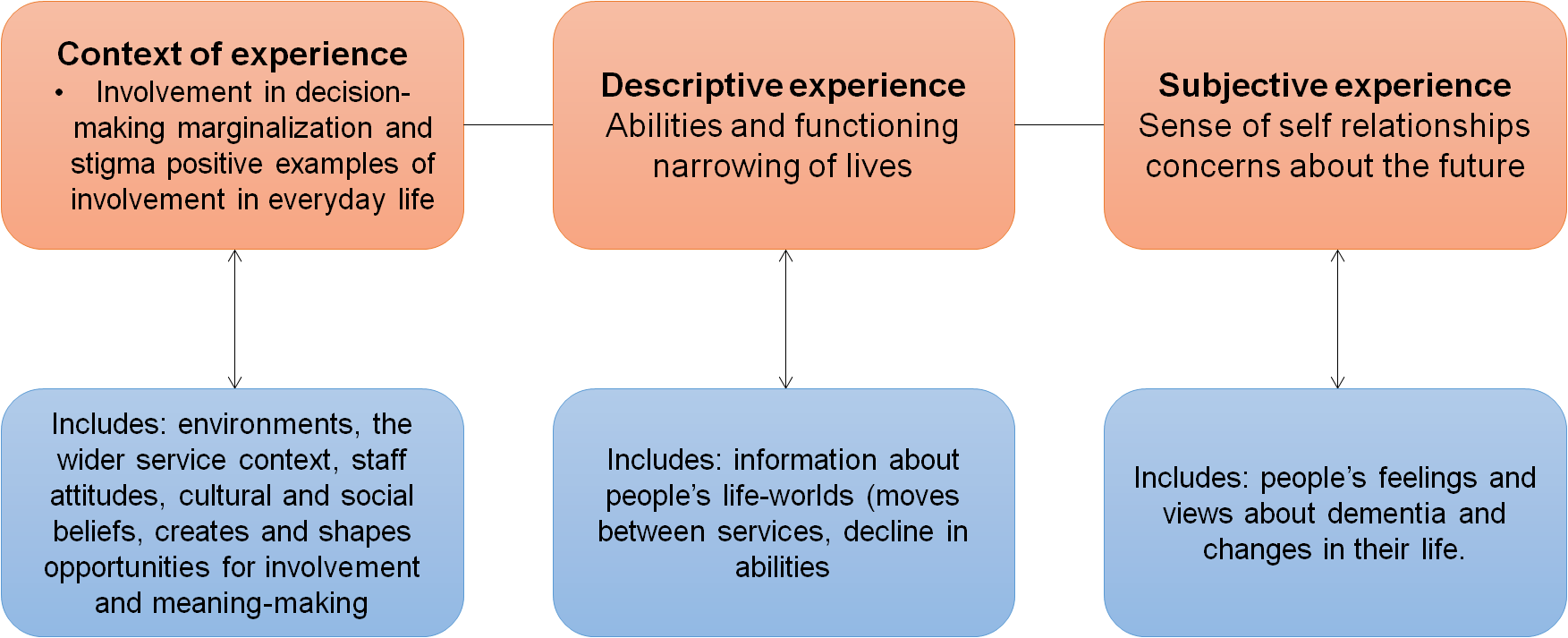

As researchers looked into the data, this research realized that the research were considering came from various perspectives. Domains included both objective events as they occurred and subjective interpretations of those events based on the participants’ feelings and attitudes. It was also clear that the larger contexts of people’s lives impacted and clarified their descriptive and subjective experiences. The many fields began to outline the expansion of topics. Figure 1 provides an outline of the areas and issues.

Figure 1. Spheres of experiences and developed themes

RESULTS

The eight dementia‐friendly community (DFC) signs that resulted from the analysis of transcriptions of interviews with relatives, caregivers, and participants with dementia-friendly were as follows: (1) proper care amenities (2) healthcare facility (3) DFC surroundings (4) journeys (5) outlets and holds (6) DFC supporters (7) incorporated information and (8) possibilities for individuals with dementia to participate in society. Dementia-friendly communities & services were shown to have the highest prevalence of sub-indicators. Indicators of possibilities for persons with dementia to offer support to and participate in their communities have produced fewer sub-indicators.

Dementia‐friendly care services

Maintain for peoplethrough dementia & their domestic caregiver that not only meets their requirements but also makes them feel secure is what this measure is measuring. Based on their knowledge, those alive with dementia & caregivers in the domestic emphasized the importance of having access to a wide variety of activities and services tailored to each person’s unique needs and preferences, all of which should be offered by entities specializing in dementia care. They emphasized the importance of being readily available, reasonably priced, and private. Caretakers also voiced the widespread sentiment that those living in facilities dedicated to dementia care should not be made to feel confined or locked up. Caregivers could improve their abilities to care for their patients by participating in these programs and services. In particular, caregivers for relatives wanted easy availability of services like non-pharmaceutical therapies for dementia patients, devices to keep patients from wandering off, welfare benefits for disabled people, assistance with finances, food delivery companies, housekeeping services, and volunteer opportunities.

Inputs for an Action

Individuals with Down syndrome who participated in the research emphasized the need to maintain a consistent routine to facilitate their engagement in group activities. They found various preferences, such as job stability, sporting leisure, music, house leadership, purchasing goods, religious activities, and social occasions. They also spoke about less common but significant events like trips and holidays spent with loved ones. Not only did this occur like the tasks themselves but also in the relative importance placed on engaging in known and unusual pursuits, seeking out chances for autonomy and receiving help, and appreciating both. The ladies stressed the need to check with caretakers before engaging in certain activities. Participants with Down syndrome acknowledged participating in a wide range of activities but highlighted the obstacles that prevented them from exercising complete control over their daily schedules.

Aid to caregivers

Caregivers understood the value of having regular workers who are familiar with their patients and have built rapport with them over time. One staff member said, “They will contact caregivers if they require anything from the shop or elsewhere.” They have confidence in us because they understand we’ll act quickly. Caregivers stressed the need for acquaintance through the person with an intelligent incapacity or dementia. Still, they also noted that comprehending how circumstances and conversations can cause adverse reactions, such as violence, anger, or disinterest, was crucial to offer efficient support. Training in open discussion, engaging personal relationships, & adapting to fluctuating care requirements were all emphasized. To offer great value care to their patients, staff, and caregivers from families stressed the necessity of open lines of communication and mutual support among all caregivers. Staff and family caregivers discussed the challenges they encounter in providing these services, including low staffing ratios, low pay, the need to finish duties other than providing care (cleaning, paperwork, etc.), a lack of education on intellectual disability and dementia, and a lack of flexibility in their roles.

Interactions with Others

Participants with Down syndrome mentioned various friendships, romantic partnerships, and familial connections. They discovered that people’s social contacts might encourage or discourage their involvement. Harmful contact with others was cited as a significant challenge; they used words like arguing, drama, unkind, and disruptive to characterize these encounters. The context of unpleasant peer interactions was emphasized but was not the exclusive focus. The effect of both good and bad social contact on persons with intellectual impairment and dementia was a common topic of conversation among caregivers. In shared housing, caregivers explored the pros and cons of interacting with peers. One caregiver highlighted the benefits of mixed-ability groups, saying, so they look out for them, referring to those with a higher level of awareness about what’s happening in the group.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Many individuals with intellectual impairments and dementia enjoy contributing meaningfully to their homes, workplaces, and communities. Future studies in this field should try to include the viewpoints of persons with intellectual impairments and dementia to maximize the information gained from their involvement. The surroundings and caregiver barriers were shown to significantly affect research participants’ ability to take part in essential duties and rituals. It’s crucial to design settings that allow for autonomy, responsibility, and mutuality, including those that allow for individual and group engagement.

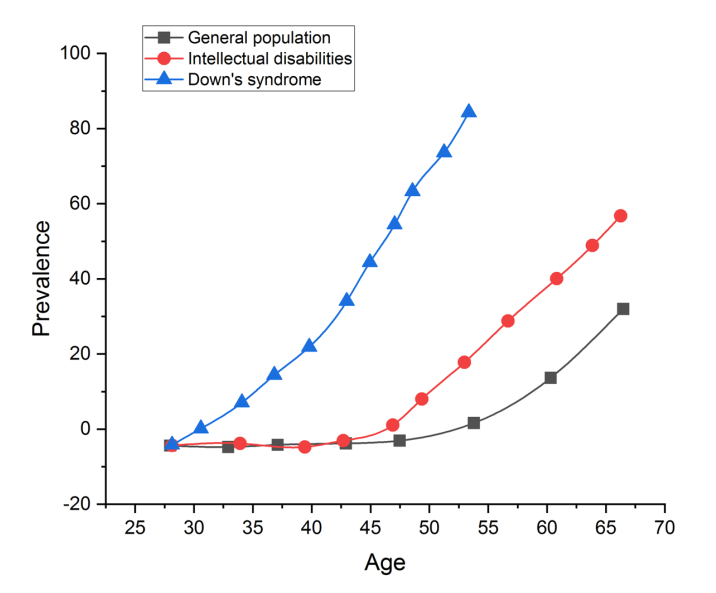

Figure 2. Comparison of dementia prevalence rates by age

Dementia prevalence rates are summarized by age in figure 2 for the general population, persons with intellectual impairments who do not have Down’s syndrome, and people with Down’s syndrome. While precision in the rates is needed, the general pattern shown here is generally recognized at this point. It has become widely accepted that persons with Down’s syndrome experience the onset and progression of dementia at an earlier age. People with intellectual impairments who do not have Down’s syndrome have a somewhat earlier age of onset of certain conditions than the average person and do not suffer from the same magnitude as those with Down’s syndrome. The last category seems to be at incredibly high risk for getting dementia, most often Alzheimer’s disease. The former type shows a broad spectrum of dementia causes.

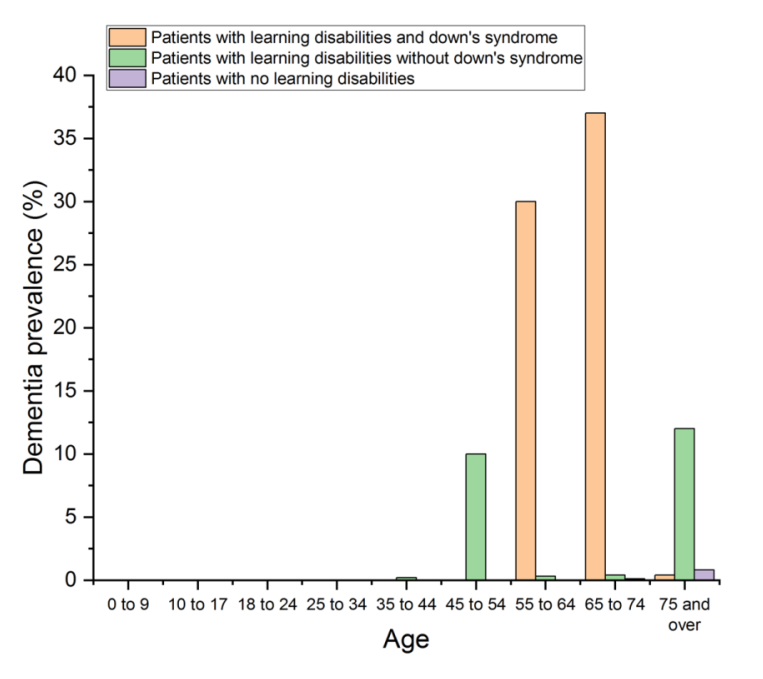

Figure 3. Dementia prevalence by age and co-morbidity of Down’s syndrome

Dementia rates among persons with learning difficulties are 5,1 % times higher than they should be based on rates in the general population adjusted for age and gender are depicted in figure 3.

CONCLUSION

Dementia patients rely heavily on their family carers to maintain a high quality of life. It is widely established that carers experience substantial amounts of emotional load and psychiatric complications and that there are risk variables that could be used to identify those who are most at risk. People with Dementia could have their quality of life enhanced by therapies that reduce the severity of these consequences. Dementia management is a team effort, including medical professionals, caregivers, and the patient’s loved ones. It is possible to identify vulnerable caregivers and tailor therapies specifically to them.

REFERENCES

1. Baruah U, Shivakumar P, Loganathan S, Pot AM, Mehta KM, Gallagher-Thompson D, Dua T, Varghese M. Perspectives on components of an online training and support program for dementia family caregivers in India: a focus group research. Clinical Gerontologist. 2020 Sep 2;43(5):518-32.

2. Ward A, Buffalo L, McDonald C, L’Heureux T, Charles L, Pollard C, Tian PG, Anderson S, Parmar J. Three perspectives on the experience of support for family caregivers in First Nations communities. Diseases. 2023 Mar 8;11(1):47.

3. Smith L, Morton D, van Rooyen D. Family dynamics in dementia care: a phenomenological exploration of the experiences of family caregivers of relatives with dementia. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing. 2022 Dec;29(6):861-72.

4. Acton DJ, Jaydeokar S, Jones S. Caregivers experiences of caring for people with intellectual disability and dementia: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities. 2023 Feb 15;17(1):10-25.

5. Xiao LD, McKechnie S, Jeffers L, De Bellis A, Beattie E, Low LF, Draper B, Messent P, Pot AM. Stakeholders’ perspectives on adapting the World Health Organization iSupport for Dementia in Australia. Dementia. 2021 Jul;20(5):1536-52.

6. McKibben L, Brazil K, McLaughlin D, Hudson P. Determining the informational needs of family caregivers of people with intellectual disability who require palliative care: A qualitative research. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2021 Aug;19(4):405-14.

7. Kagwa AS, Konradsen H, Kabir ZN. Value co-creation with family caregivers to people with dementia through a tailor-made mHealth application: a qualitative research. BMC Health Services Research. 2022 Nov 16;22(1):1362.

8. Herron DL, Priest HM, Read S. Supporting people with an intellectual disability and dementia: A constructivist grounded theory research exploring care providers’ views and experiences in the UK. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2020 Nov;33(6):1405-17.

9. Malhotra C, Hazirah M, Tan LL, Malhotra R, Yap P, Balasundaram B, Tong KM, Pollak KI, PISCES Research Group. Family caregiver perspectives on suffering of persons with severe dementia: A qualitative research. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2021 Jul 1;62(1):20-7.

10. Masoud S, Glassner AA, Mendoza M, Rhodes S, White CL. “A different way to survive”: The experiences of family caregivers of persons living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Nursing. 2022 Aug;28(3):243-57.

11. Sanford S, Rapoport MJ, Tuokko H, Crizzle A, Hatzifilalithis S, Laberge S, Naglie G, Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging Driving and Dementia Team. Independence, loss, and social identity: Perspectives on driving cessation and dementia. Dementia. 2019 Nov;18(7-8):2906-24.

12. Fetherstonhaugh D, Rayner JA, Solly K, McAuliffe L. ‘You become their advocate’: the experiences of family carers as advocates for older people with dementia living in residential aged care. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021 Mar;30(5-6):676-86.

13. Balouch S, Zaidi A, Farina N, Willis R. Dementia awareness, beliefs and barriers among family caregivers in Pakistan. Dementia. 2021 Apr;20(3):899-918.

14. Harris ML, Titler MG. Experiences of family caregivers of people with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Western journal of nursing research. 2022 Mar;44(3):269-78.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

FINANCING

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Komal Patel, Bikrant Kumar Prusty J, Tarang Bhatnagar, Abhinav Mishra, Jamuna KV, Ajit Kumar Lenka, Dhanaji Wagh.

Investigation: Komal Patel, Bikrant Kumar Prusty J, Tarang Bhatnagar, Abhinav Mishra, Jamuna KV, Ajit Kumar Lenka, Dhanaji Wagh.

Methodology: Komal Patel, Bikrant Kumar Prusty J, Tarang Bhatnagar, Abhinav Mishra, Jamuna KV, Ajit Kumar Lenka, Dhanaji Wagh.

Writing - original draft: Komal Patel, Bikrant Kumar Prusty J, Tarang Bhatnagar, Abhinav Mishra, Jamuna KV, Ajit Kumar Lenka, Dhanaji Wagh.

Writing - review and editing: Komal Patel, Bikrant Kumar Prusty J, Tarang Bhatnagar, Abhinav Mishra, Jamuna KV, Ajit Kumar Lenka, Dhanaji Wagh.